New York Rents Are Sky High. Legislative Relief is Dead. What Happened?

Housing activist Cea Weaver talks about why tenant protections failed to pass this year, and what New York should be doing to build more affordable housing.

4:06 PM EDT on June 2, 2022

(Hell Gate)

New York City tenants continue to endure blistering rent increases in the worst housing market in modern history. But on the last day of the state's legislative session, lawmakers have declined to take up legislation that would provide renters throughout New York with relief.

The bills, known as Good Cause, or Good Cause Eviction, would prevent landlords from evicting tenants without a clear justification, and would restrict how much they can raise the rent every year.

Cea Weaver, a housing activist and campaign coordinator for Housing Justice for All, got back into the city from Albany on Wednesday night. When we spoke with her Thursday morning, she had just gotten word that Good Cause was being discussed in a Senate conference committee, which can be a precursor to a vote. But on the last day of session, it seemed more symbolic.

"My guess is that they're conferencing it because they want to prove that it doesn't have support, because we're all pissed about it not passing," Weaver theorized. "Albany is so conspiratorial."

We asked Weaver, whose nomination to the City Planning Commission was withdrawn last year after forceful objections from the real estate industry, about why Good Cause failed, how affordable housing should be built in New York City, and what tenants can do about the ongoing crisis.

This interview has been lightly edited and condensed for clarity.

You've been tweeting about people's astronomical rent increases, we published a story on it last week, and yesterday, one of my friends texted me their rent was going up $625 per month. Landlord groups have said that they need to cover costs, so they have to raise rents. What do you think is behind these huge rent hikes?

One, there is this COVID deal situation where people left the city, landlords wanted them to stay, and landlords offered deals. The second reason is that there's a lot of demand. People are coming back to the city and landlords can raise the rent, so they are. I really don't think it's about covering costs. It started happening, and once it started happening, all these landlords are seeing it happen and they're like, I could try that. And it's working. And we don't have Good Cause Eviction!

A third is that—I can't tell if this is overblown or not—but I do think that there's backlash to the two years of the eviction moratorium. Landlords would rather just raise the rent and try to recoup more quickly than apply for ERAP. I think some of the professionalized landlords, like the REBNY members, are totally happy to get vouchers and have rent be paid by any means.

But I think there's a lot of people who, ideologically, were activated during the pandemic when they were told they couldn't evict people, who don't want to interact with government programs to get their rent paid, and so don't really want ERAP—and don't want to go through the trouble and would rather just try to recoup as much as they can right now.

I just got off the phone with my sisters old roommate who just received a 30 day notice of a $400 rent increase.

— Allie wants statewide #GoodCause (@ADentinger15) June 1, 2022

I sadly had to inform her that not only was this completely legal but also that it’s become super normal for tenants in NY.

😡 🧵

1/5

What's the mood in Albany like right now?

I think the mood is basically fear of a conservative backlash, especially in the Senate, to some of the stuff that they've been doing. Everyone is not sure what their district is. That's less true in the Assembly, but the Assembly is complicated. The Assembly has never led on housing issues, so we really do rely on the Senate to pull the Assembly along. And the mood in the Senate is totally frozen in place and totally fearful that they're going to lose their marginals, and it's stupid.

In 2019, the state legislature passed major reforms, and it was a huge year for housing activists and tenants. The rental crisis is worse now than it was then, and yet lawmakers aren't taking it up. Is the big difference between then and now just redistricting?

The Assembly thinks that they already dealt with the issue. And the fact that the [2019] rent laws did not happen in an election year is a very convenient excuse for [Deputy Senate Majority Leader] Mike Gianaris. And 2019 was not an election year, 2022 is, and I think in the Senate, they're very afraid. Between the maps and REBNY spending, they don't want to piss off REBNY.

Something that [lawmakers] keep telling me is [that] they have to keep the supermajority in order to do things like Good Cause, and so I should be patient because in January, the supermajority will be ensured for another two years and we can do good things again. I think that that is really, really, really misrepresenting what's going on here, because I don't think that rightwing voters are animated by tenant protections. I think real estate owners are, and small landlords are too. But you know, the Senate and the Assembly are passing a big gun control package. That's the kind of issue that animates regular rightwing, working-class people. And so I think when they say that they don't want to give conservatives a reason to vote against them, they really mean they don't want to give real estate a reason to spend against them.

The last thing I would say that the difference between 2019 and now, and it seems a little silly, but I think it’s really actually true: in 2019, I think REBNY was just fully caught unawares. And not just REBNY—CHIP, whatever—they were fully caught unaware; they were not expecting what happened to happen. Since then, they've been organizing—and they spent a lot of money this year against Good Cause, like, tons and tons of money against Good Cause.

And two years of the eviction moratorium really radicalized the petty bourgeois landlord-type person, "mom-and-pop" landlords. Those combination of factors made it really hard to move Good Cause here.

The 2019 reforms stopped the bleeding a bit with respect to rent-regulated units, while Good Cause targets unregulated, or "market-rate" units. Is it fair to say we're talking about two different classes of housing altogether?

We're talking about different types of housing and also a much lighter form of regulation. Good Cause Eviction doesn't really cap rent. It's a defense that a tenant can use if they fall behind on rent in a non-payment case. Your landlord could raise your rent and you could write them a letter saying, “Hey, you know, this is illegal, I'm not going to pay it.” Then they would say no, you'd fall behind in rent, and they'd take you to housing court. You'd raise Good Cause as a defense in that non-payment case and a judge would decide what the deal is.

That requires tenants to be really, really willing to stand up and fight for their rights. Obviously, if we got Good Cause we would pivot to organizing tenants to educate them about their rights. But actually, most people will just try to pay the rent increase because they wouldn't know about it. All these other housing interventions that we've tried—ERAP, Section 8—don't really work because landlords don't have to give a reason for eviction.

I'm talking with a family who lives in Sunset Park. The woman got pregnant and the landlord wants them to leave, because it is kind of annoying for other tenants to have a baby in the apartment. The tenant wants to prove discrimination, because it's discriminatory. You can't evict someone based on their family makeup; that's protected under the Fair Housing Act under federal law. But it's impossible for her to prove this, because the landlord doesn't have to give a reason for why they're rejecting this unregulated tenant. And so Good Cause really is an enforcement mechanism for all sorts of other long-standing housing protections.

NOW: Tenants are back in Albany to rally for #GoodCause—a massively popular measure supported across all regions in New York.

— Housing Justice For All (@housing4allNY) May 31, 2022

But @GovKathyHochul and lawmakers have chosen their corporate landlord donors over millions of working families. pic.twitter.com/b2aDPFX8qu

Turning to the supply-side part of the rent crisis: What do you make of the developer pulling the One45 project in Harlem? That development would have been 457 totally unregulated units, and 458 apartments with varying degrees of "affordability." The councilmember there was opposed, some members of the community were opposed, and some affordable housing advocates were left frustrated that this won't get built.

I don't know. I think the politics on this have gotten really challenging. That's a giant building—50 percent market rate, 50 percent affordable. I really think it's irresponsible and bad for the city that we are just trying to solve the affordable housing crisis on a site-by-site basis. We really opposed a lot of the de Blasio rezonings because they didn't go far enough. And in retrospect, neighborhood-based rezoning to encourage the production of low-income housing isn't the worst thing in the world. And it's maybe the best we can do with the current tools that we have.

I would really like for us to have a publicly backed affordable housing developer who is able to build housing at a variety of income levels across the state. HPD and HCR basically function as a bank for property developers who can acquire land and then take out low-cost loans from the city in order to make it affordable. I would think that it would be better and more direct if we could just build housing ourselves. And that's what we should be striving for. And we're going to need to do that at a variety of income levels, including very, very-low income, up to housing for teachers and nurses and working-class and middle-class people.

The One45 stuff is so hard because neighborhood residents are not really going to be able to move into One45, even if it was 100 percent affordable, because it's simply not that much housing. The demand will just far outpace the supply and no one's going to see it as something that's meaningfully impacting them. There's just so much power in the hands of single city councilmembers to kill site after site after site. And it's easy to see why there's no political support for projects like that and why it's easy to just get them killed. It's hard to make the case that One45 is going to meaningfully address the city's affordable housing problem, because it's not.

I think the only way we can really do this is if you make some commitment to a city-wide number that neighborhoods are all going to share. We have to detoxify it by taking the real estate profit question a little bit out of the equation.

I honestly think Good Cause will help. The fear of displacement that happens when they try to create a higher market in the neighborhood is real. And I personally believe that we need a lot more housing, and Good Cause helps to create the political conditions to fight for that.

Earlier, you said we need a "publicly backed" housing builder. Do you mean that the government needs to get in the business of building housing? How do we get to that point? Doesn't federal law prevent us from doing that?

No. Federal law prevents federal money from being used for it, but you can do all sorts of things. First of all, I think that we're lucky in New York because we have a public housing authority that actually wants to own housing, unlike most public housing authorities across the country which have already gotten rid of most of their stock. There's a lot of people who know how to run housing, who live and work in our City's bureaucracy—and that's a good thing, because knowing how to manage housing is actually a skill, especially if it's a 600-unit building. I don't know how to do that and I'm not going to pretend to.

We have all the tools that it takes here. And what I'm envisioning is—and what I think a lot of people thinking about this social housing question are envisioning—is a big sort of municipal land trust that owns land, that builds housing, and it could be a rental that's owned and operated by the municipal land trust. Or it could be like a shared-equity cooperative, where the housing is sort of permanently and publicly stewarded, but there is a sort of limited and collective equity as part of the equation.

The main task here is this question of long-term stewardship and who is going to be able to earn equity and profit from the increasing value of land in the city. And that should, as much as possible, be the City itself or the people who live in the housing, not a private developer.

Let's assume Good Cause is dead today. What should people do? Some people I know are literally praying for a recession or a real estate crash to cool things off. Where do tenants go from here?

It's hard. You can always fight your rent increase—you can come together with your neighbors, you can try to negotiate with your landlord. It's easier if you're doing it in a tenant association and you can say, "Hey, I want to negotiate down my $400 rent increase, or my 100 percent rent increase." We're going to try to put together a toolkit in the coming weeks for how people can do that. The first step is: Talk to your neighbors. Write a demand letter. It's really scary, right?

There are also ways that you can try to, in court, take advantage of the City's new right to counsel of laws that have been recently expanded to cover the whole city and people at higher income levels. You can try to prove retaliation, if your landlord is seeking to not renew your lease. There are existing provisions that people can try to use, but they're not that easy to use, which is why we really want Good Cause.

We want people to not let the legislature get away with doing this. To me, it's really just immoral that in the middle of a very clear and present crisis, they're choosing inaction because they're afraid of REBNY backlash. It's so dumb. Are they not getting the same phone calls that I'm getting? Obviously not. So we really need to do whatever we can to politicize this crisis and to make the leadership in the legislature feel accountable for everyone's giant rent hikes.

Thanks for reading!

Give us your email address to keep reading two more articles for free

See all subscription optionsChris is an editor at Hell Gate. He spent a decade working for Gothamist, and his work appears in New York Magazine and Streetsblog NYC.

Stay in touch

Sign up for our free newsletter

More from Hell Gate

A Fired Google Engineer on Protesting the Company’s ‘Terrible Path in Their Pursuit of Money at the Expense of Human Life’

Zelda is part of a group of workers fired after participating in last week's No Tech for Apartheid demonstration.

Two West Village Newcomers Bring Fresh, Delicious Energy to the City’s Increasingly Predictable Burger Game

Burgerhead and Smacking Burger (located in a gas station) surprise and delight with their simple pleasures.

Eric Adams Still Wants to Cut Library Funding—But Don’t Worry, We’re Getting 1,200 More Cops

And more news for your Thursday.

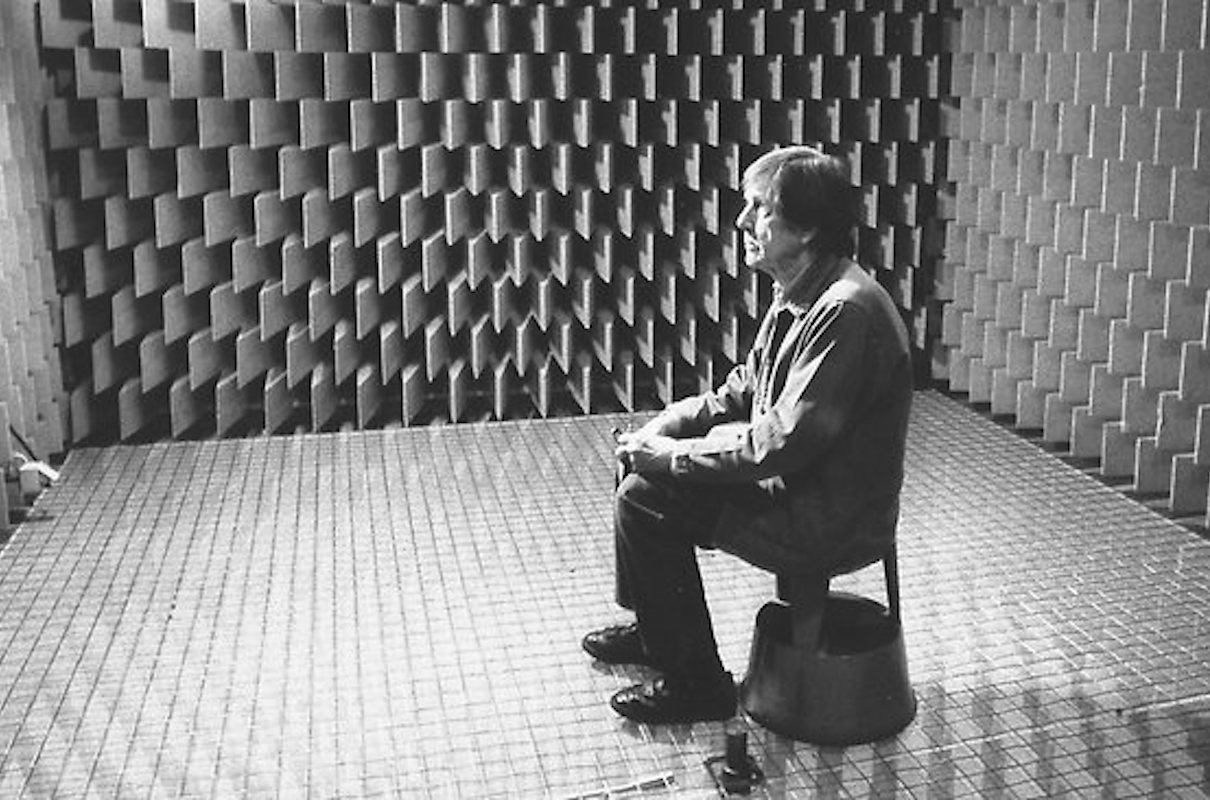

This NY Times Columnist Should Probably Not Be Teaching John Cage to Columbia Students

John McWhorter can't be serious. He just can't be.

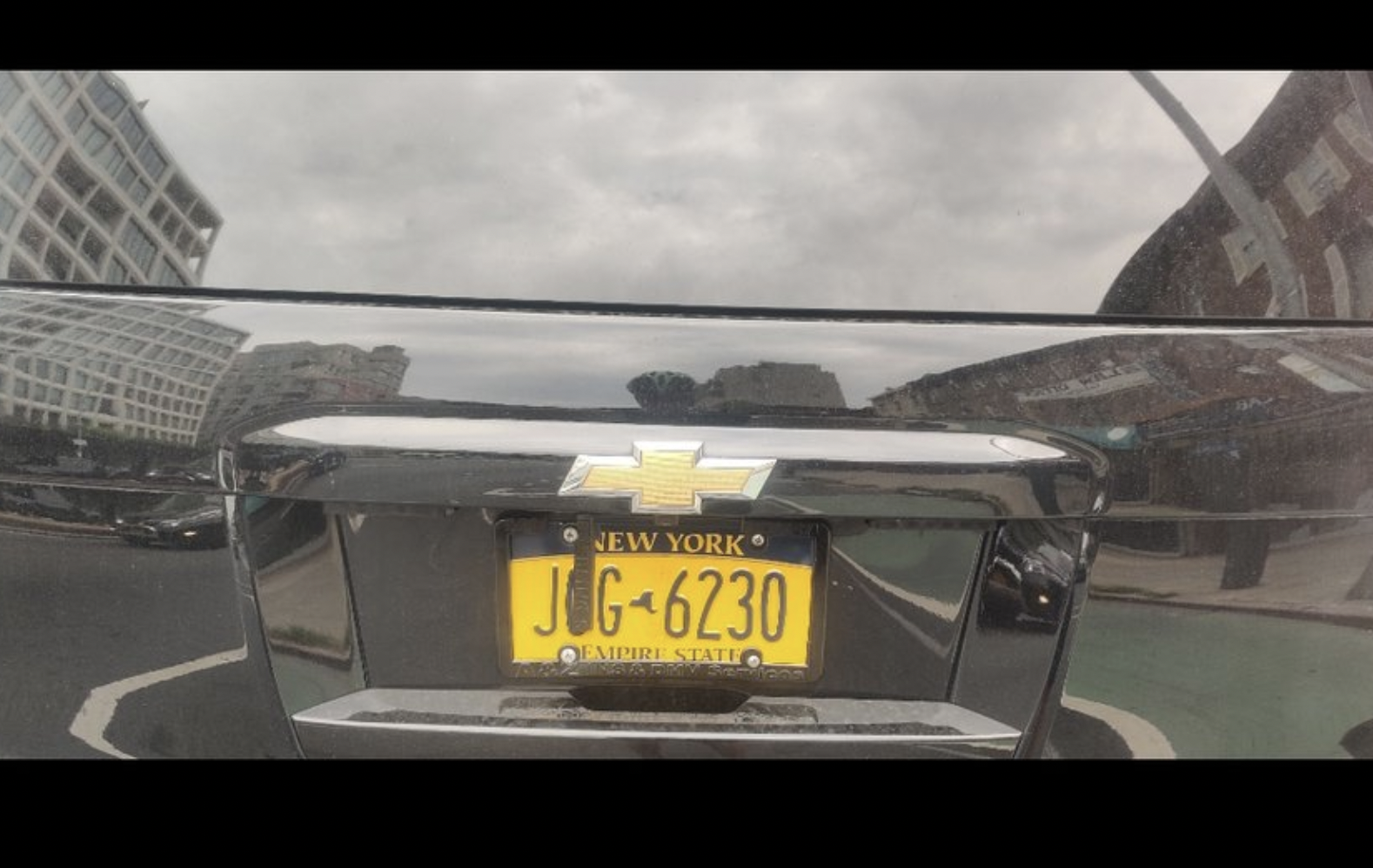

One Weird Trick for Getting Away With Obscuring Your License Plate

New York state lawmakers increased penalties for toll scofflaws, but also explicitly gave cops the power to cut them loose.