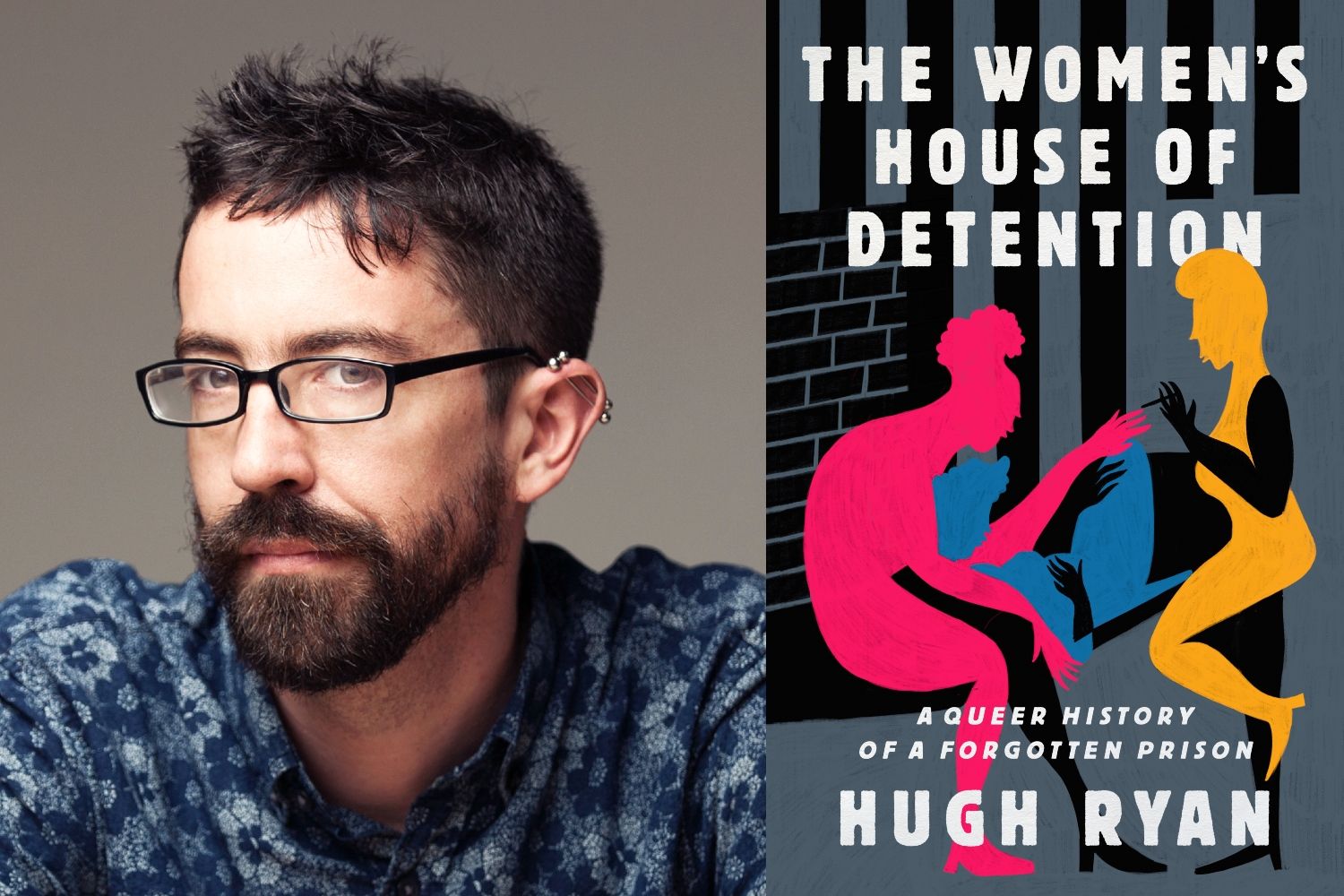

The following is an excerpt from historian Hugh Ryan's "The Women's House of Detention: A Queer History of a Forgotten Prison," on sale Tuesday, May 10. In it, Ryan traces the history of a largely forgotten prison in New York City's Greenwich Village and makes clear that "by queering the Village, the House of D helped define queerness for the rest of America."

On the night Mabel Hampton was arrested the weather was, in a word, "unsettled": cloudy and warm, with winds that spent the whole day twisting back on themselves, flying up the long avenues of Manhattan from the southwest before doing a 180 to catch you from the north side too. It was July 5, 1924, on 123rd Street: the heat of summer, in the heart of Harlem, as the twenties roared—a moment of unimaginable potential for a young Black lesbian like Mabel Hampton, who could find friends, lovers, a job, or an all-Black party around any corner.

But it was a moment of great danger as well. Before the night was over, the state would steal the next three years of her life.

From the police file of Mabel Hampton: "A small rather bright and good looking colored girl. 21 years old but appears to be younger. Has bushy black hair, is slim but not lacking in nourishment. Dark brown eyes. Friendly. Alert. Composed. Pleasant voice and manner of speaking."

In actuality, Hampton had just turned twenty-two a few months before her arrest. How do we know this? Because Hampton had the (rare) opportunity to record her side of the story.

In many ways, Hampton's life was typical for working-class women of her day. Like most of her contemporaries, she entered the historical record the moment she was arrested, throwing her into a diffuse network of police, jails, courts, prisons, hospitals, reformatories, and social service organizations, all of which kept copious files. Unfortunately, many of our oldest and most extensive records of queer history come from our carceral system, and they are some of our most homophobic and ignorant ones as well. While they provide data—names, addresses, ages, etc.—they lack real descriptions of the experiences, feelings, and thoughts of the people they chronicle, and depending on the diligence of the individual who created them, carceral files contain many errors, small and large.

But in another way, Mabel Hampton was a true trailblazer—an out, Black, working-class lesbian dedicated to developing queer community. Through the connections she forged, her story has been preserved in greater and more personal detail than any of her contemporaries', and her work helped pave the way for the Lesbian Herstory Archives, where her story lives on today in a series of oral histories done in the 1970s and '80s.

The dynamic tension between her two sets of records—one produced about her and one produced by her; one contemporaneous and one retrospective; one for straights and one for queers—creates an incredibly robust picture of Hampton's life, while simultaneously highlighting the limits of each record when examined independently.

A few months before her arrest, Hampton had been cast as one of the "bronze beauties" in the chorus of "Come Along Mandy," a popular musical farce at the Lafayette Theater, a pillar of the Harlem Renaissance. "Mandy" was known for casting chorus girls who weren't lightskinned, women who were "dark clouds" or "smokey joes" rather than "high yellow" or "red bone," according to the argot of the Black theater at the time. Backstage, Hampton met some of the most famous Black queer women in showbiz, from Gladys Bentley, to Ethel Waters, to Jackie "Moms" Mabley. But the theater was a come-and-go job, and generally, Hampton remembered, she would go as soon as the men came on to her. Every show she worked, she said, "some man would feel my pussy and I’d have to leave."

Like many working-class women, Hampton often held multiple jobs simultaneously. When she wasn't dancing in the chorus, she did domestic work, living with white families, taking care of their apartments and children—which is why she was on 123rd Street that night, in an apartment belonging to Mrs. V. K. Howard. Howard and her children were in Europe that summer, and Hampton managed their apartment in their absence. The night before, to celebrate July 4th, she and her girlfriend Viola had gone to a cabaret, where they met a white man who asked to call on them the next evening. He'd bring a friend, he said. Meet them at Howard's apartment. Take them out for a Coke.

In the end, Abraham Schlucker brought two friends: Patrolmen Dorfmen and Holmes of the NYPD, who burst through the doors of the apartment and arrested Hampton and Viola. The charge? Violation of Section 877, subdivision 4 of the New York Code of Criminal Procedure: vagrancy prostitution. Of the 17,000 women arrested in New York that year, one in eight was arraigned for vagrancy prostitution, and hundreds (perhaps thousands) of others were arrested on sex-work-related charges. Queer working women like Hampton were in particular danger because one telltale sign of prostitution, according to police informants, was being a woman out at night without a man.

Like the vast majority of other women arrested in New York City at the time, Hampton was quickly whisked down to Greenwich Village, which was, throughout the twentieth century, the epicenter of women’s incarceration in New York, and the epicenter of queer life in America. These two histories twine round each other like grape vines—twisting, interconnecting, and reinforcing one another, until it’s impossible to tell where one ends and the other begins.

Yet for too long, only half the story has been told. The whiter half, the richer half, the half concerned with famous artists—and, mostly, the half about men.

To understand what happened to Mabel Hampton on the night of July 5, 1924, and how women like her created the Greenwich Village we know today, requires drawing together thousands of threads, stretching to the furthest bounds of America's global empire and going back almost to the founding of this country. The history of women’s incarceration is not simply a small mirror held up to the incarceration of men; rather, it is about the development of a distinctly unjust system of justice, violently dedicated to the maintenance and propagation of "proper" femininity.

Mabel Hampton was arrested five years before the Women's House of Detention was built. But it was built for women like her, and because women like her were increasingly a part of civil society, whom the government wanted to control. In fact, Hampton was brought to Greenwich Village by the same forces and laws that were already working to build "the House of D."

Women like Hampton, arrested in the years immediately preceding the construction of the Women's House of Detention, were the ones for whom the House of D was created. Simultaneously, they were the ones who had the least say in its creation. But without them, the House of D would not exist: not as a building, nor as a landmark. The state built the House of D to hold these women and transmasculine people, but they are the ones who invested it with meaning. Like others in the 1960s, Hampton found ways to turn the state's carceral infrastructure to her advantage. The prison would never be anything more than a prison, but the people inside it were always so much more than "prisoners."

This article has been adapted from "The Women’s House of Detention: A Queer History of a Forgotten Prison" by Hugh Ryan. Copyright © 2022. Available from Bold Type Books, an imprint of Perseus Books, LLC, a subsidiary of Hachette Book Group.